Painted Portuguese Tiles called Azulejos

Elaborately-painted Portuguese tiles called Azulejos fell out of favor in the early 20th Century. But Lisbon today is embracing the art in its murals, museums, and metro stations.

Thank You: BBC Travel: Arts and Architecture 2014 Written by David Whitley

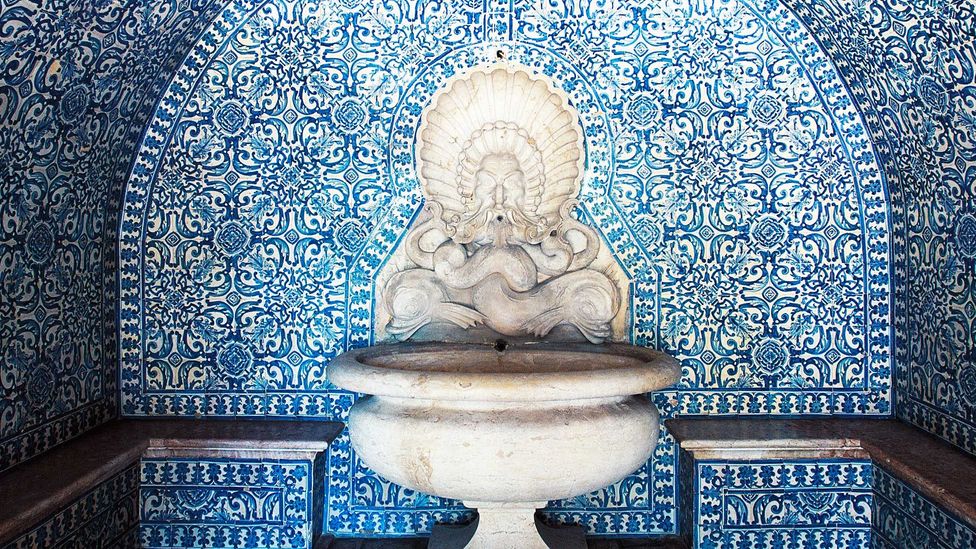

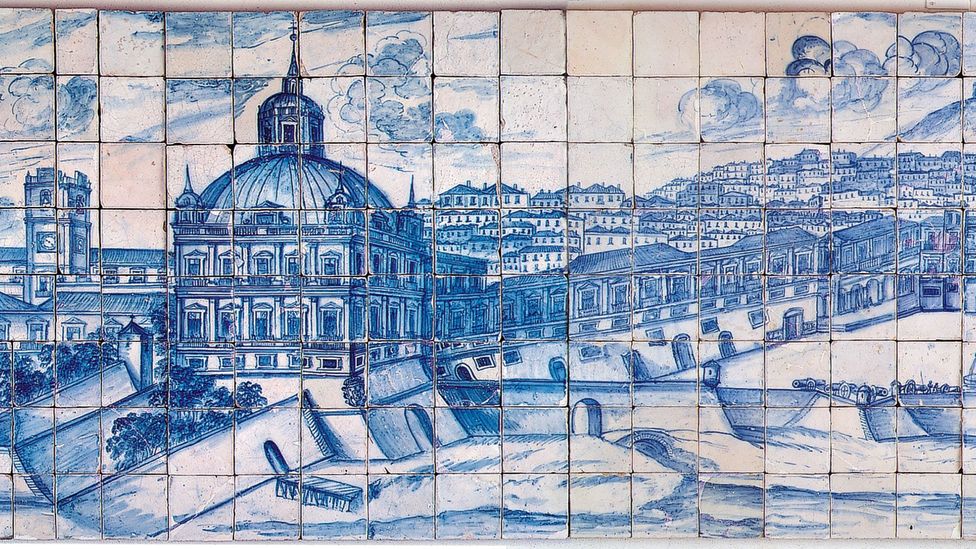

The blue-and-white tiles that line the church of Lisbon’s Madre de Deus convent complex tell stories in engrossing detail: Moses and the Burning Bush, the life of Santa Clara, and the works of St Francis of Assisi. The tiles, called Azulejos, are not only compelling, but they are also uniquely Portuguese – which is why, in 1971, the convent became the centerpiece of the Museu Nacional do Azulejo, a museum dedicated to preserving tile art from around the country and across the centuries.

Azulejos first came to Portugal in the 15th Century, when parts of the Iberian Peninsula were still under Moorish rule. Although many assume the word is a derivation of Azul (Portuguese for “blue”), the word is Arabic in origin and comes from az-zulayj, which roughly translates as “polished stone”.

“Many other countries have tile art, where it is used as decoration like a tapestry,” said museum director Maria Antónia Pinto de Matos. “But in Portugal, it became a part of the building. The decorative tiles are a construction material as well as decoration.”

Lisbon’s ubiquitous Azulejo-clad buildings are not all centuries-old work, though. In fact, in the early 20th Century, Azulejo art had fallen out of favor. “The cultural elite despised it and said it was for the poor people,” said Nuno Pereira, the head of international affairs for Lisbon’s metro system. But an Azulejos revival started in the 1950s when Lisbon’s first metro station designers wanted a low-maintenance, easy way to have the underground spaces feel less separate from the outside world.

Parque and Restauradores stations, the most impressive examples among the seven originally built stations, are covered in geometric-patterned tile, many of which are the work of the prolific Portuguese artist Maria Keil, whose husband Francisco Keil do Amaral was the stations’ architect. Her decorative flair now features in 19 of Lisbon’s stations.

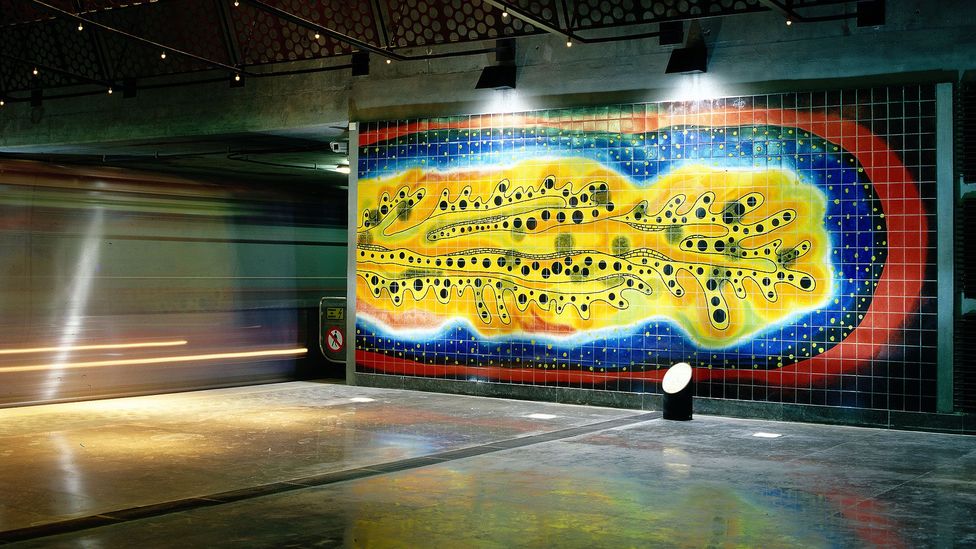

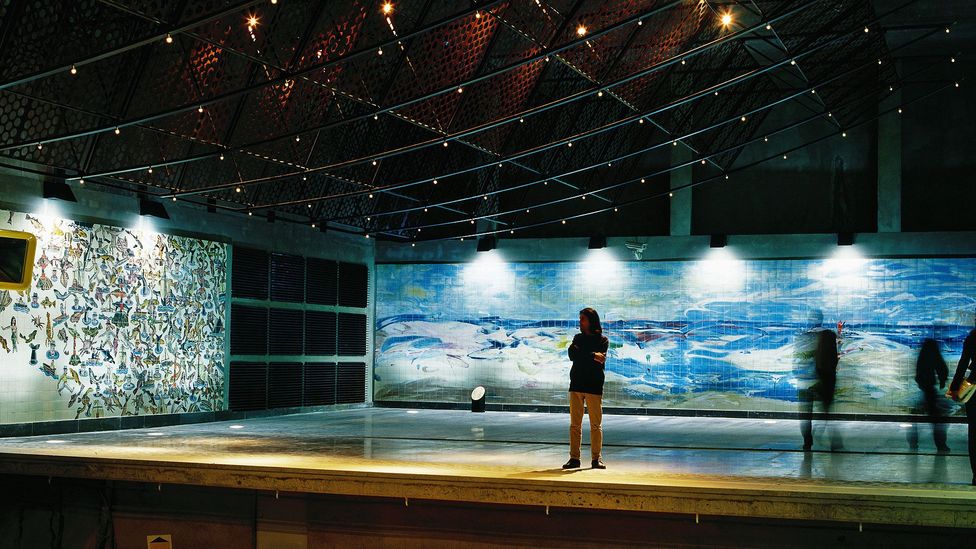

If Keil’s work helped revive azulejo interest, then the 1998 World Exposition transformed the art itself. When Lisbon was awarded Expo ‘98, city authorities decided that a formerly derelict riverside site was the ideal place to house the international showcase – and that a new metro line was needed to connect the site to the city, providing several additional outlets for Azulejo artists to show off. Out went Keil’s safe geometric designs; in came storytelling. At Alameda Station, Costa Pinheiro added images of navigators and ships to reflect Portugal’s seafaring history. At Olivais, Nuno Siqueira and Cecília de Sousa painted olive trees on the tiles, representing the grove that once stood in the location. And at Oriente, the exit station for the Expo site, artists from five continents were given their own space to create individual works with a linking maritime theme.

Since then, tile art has been installed in numerous other metro stations. At Cais Do Sodre, giant Alice In Wonderland-Esque rabbits cover the train tunnel. At Alto do Moinhos, goats butt heads, writers brandish quills, and a donkey bucks.

Many of the newer works dotted around Lisbon and the rest of Portugal are collaborations with the Galeria Ratton, which opened in 1987. Located just west of the Bairro Alto district, the gallery’s frequently changing exhibitions showcase local and international tile artists, and it facilitates major public installations like those in new train stations across Portugal. “The main objective was to close the gap between contemporary art and traditional tile painting,” said gallery co-owner Tiago Monte Pegado. “It’s about discovering a new form of expression. We never take a drawing that already exists – it’s always new for the tiles.”

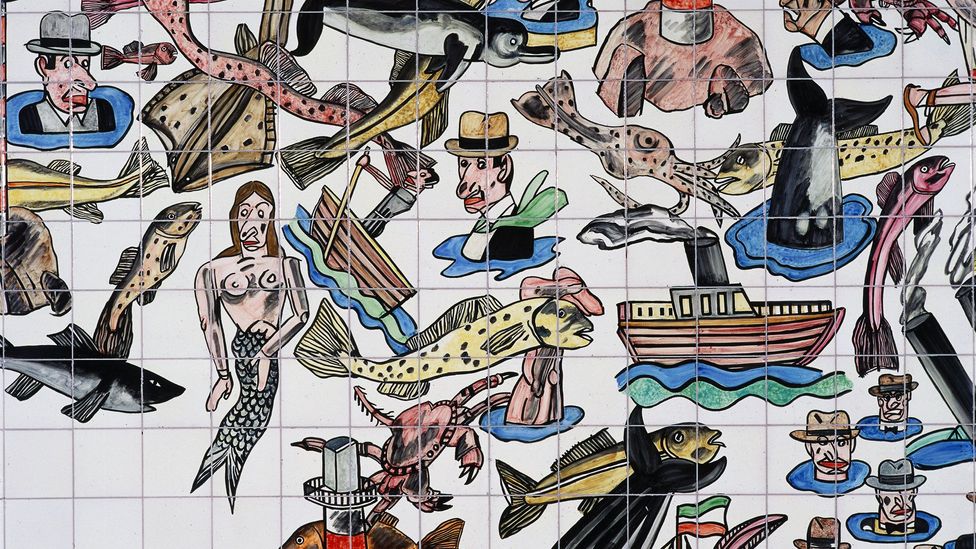

Helping major azulejo artists get together with organizations that want to commission works is part of what Monte Pegado calls “the democratization of access to art”. Paula Rego’s scene of a phoenix rising from the flames graces the gardens of the 17th-Century Fronteira Palace, while Menez’s overlapping scenes of women dancing in circles brighten up the playground at Praça Marcos Portugal. At Praça do Comércio – the giant square that links Lisbon’s city center to the waterfront – the entrance to the newly opened (and admittedly touristy) Museu da Cerveja features a dizzying joyful tile mural by Júlio Pomar. A rabbit tucks into a watermelon, a man plays the mandolin and all manner of other oddities merge into a surreal whole.

Menez’s dancing women. (David Whitley)

A sign nearby says: “What has been painted on the wall is there to entertain – a juggling trick; a street performance. It’s as simple as that.”

It’s not quite a centuries-old depiction of Moses and the Burning Bush, but if Azulejos are being commissioned for pure fun, then the traditional art form is in good health.

Influences in Maienza Wilson Projects: Spanish Colonial Revival in Highland Park, Texas. We enjoyed our visit to Lisbon and learning about this very special tradition.

Painted Portuguese Tiles called Azulejos, Lisbon, Portugal

Lisbon, Portugal, Azulejos

Painted Portuguese Tiles called Azulejos, Lisbon

Lisbon, azulejos, Portugal

Lisbon, azulejos, Portugal

Lisbon, Portugal, azulejos

Lisbon, Azulejos, Painted Portuguese Tiles

Painted Portuguese Tiles Called Azulejos

Lisbon, Azulejos, Portugal

Lisbon, Azulejos, Portugal

Azulejos, Lisbon, Portugal

Lisbon, Azulejos, Portugal